Victor Carl, Paula, Gertrud, Walter and Kurt Oppenheim

Akazienweg 7 (Engelsburg-Gymnasium)

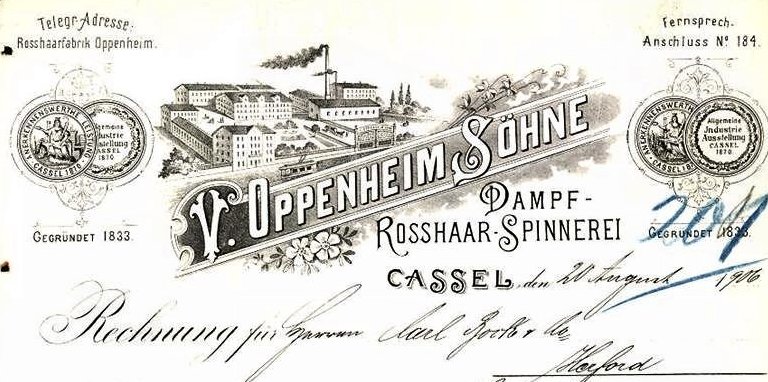

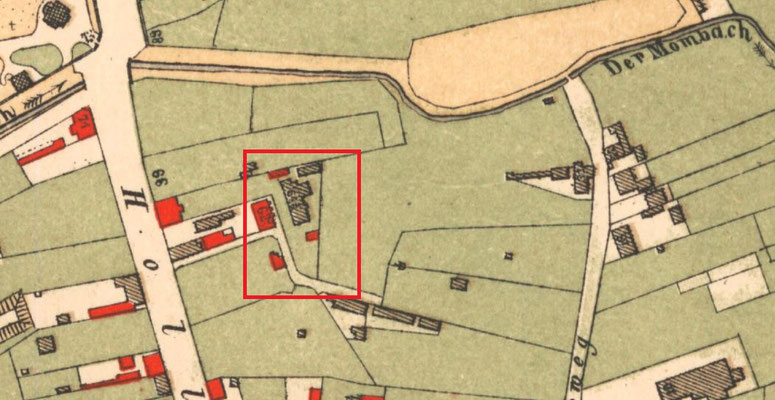

In 1911, Nathan Oppenheim from Kassel expressed his attachment to his Jewish home community of Reichensachsen by donating a Torah curtain for the synagogue. His family had moved there from Kassel in 1867 at the latest. The Kassel address book for that year contains the first entry for Nathan's father, Victor Oppenheim (1807-1880), ‘manufacturer, horsehair spinning mill, furniture belt and twine factory at Holländisches Thor 31 ¼.’

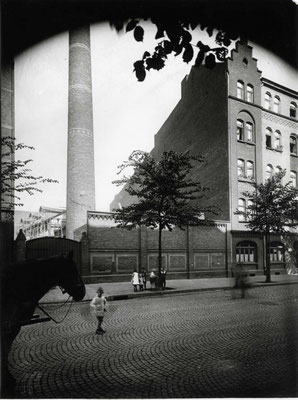

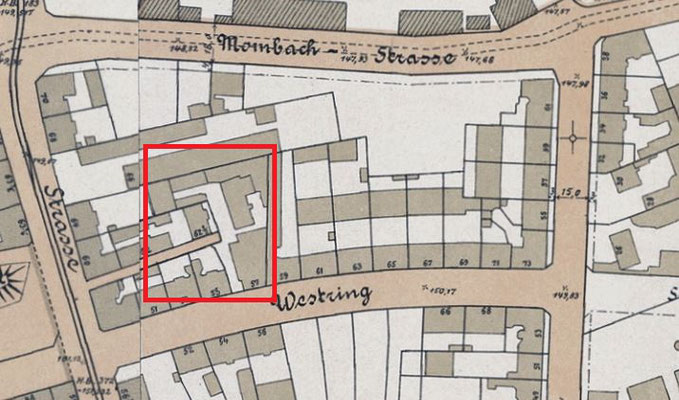

The company, founded in 1833, obviously expanded with the economic upswing following the annexation of Kurhessen by Prussia and the founding of the German Empire, and was to remain at Holländische Straße/Westring until after the Second World War.

It was a tradition in the family that the eldest sons joined the management. They also passed on their grandfather's name to their eldest sons, in addition to another first name. In the mid-1920s, cousins Victor Carl and Victor Nathan Oppenheim were the sole owners of the successful company, which primarily produced fillings for upholstered furniture, beds and, later, increasingly for the automotive industry.

Top left: the letterhead of the Rosshaarspinnerei (horsehair spinning mill) from 1906 – top right: view of the spinning mill from Westring, 1920s, Murhard Library

Bottom left: Neumann city map, 1878 – bottom right: city map, 1910 (thanks to Alexander Link)

Victor Carl, born on 9 July 1885, was the eldest son of Meier gen. Max Oppenheim (1852-1939) and his wife Johanna. While his younger brother Leopold studied law and became a lawyer (he was to be the last chairman of the provincial council of the Jewish community), Victor Carl joined the company and received a thorough commercial education – partly in companies abroad with which the horsehair spinning mill had business relations. In 1912, he married Paula Löser, born on 28 October 1888, the daughter of department store founder Ferdinand Löser (1852-1920) and his wife Marianne, née Levy (1856-1935), who came from Hamburg. After the war, Paula described herself in her youth as an athletic woman who did gymnastics, swam, played tennis for ‘Rot-Weiß’, took part in fox hunts as a horsewoman and was also a recognised motorist – an expression of her family's social status.

The couple had three children: Gertrud (born in 1913), Walter (born in 1917) and Kurt (born in 1919). As a soldier in the First World War, Victor Carl was awarded the Iron Cross. In her CV for her Abitur (A-levels), his daughter Gertrud described how she saw him on home leave with his arm in a sling as a wounded soldier.

In the early 1920s, the family purchased the extraordinary villa at Akazienweg 7, built by the building materials dealer Scheldt, from his heirs. The family of five lived here – assisted by a maid and a cook – in 14 rooms, some of which were magnificently decorated. These included mosaics with motifs from Roman times, which probably appealed to Victor Carl's obvious interest in history.

Above: Victor Carl Oppenheim, his wife Paula (née Löser) and an interior view of Villa Scheldt around 1890 (Historical Photo Collection of the Murhard Library)

Below: Photographs taken at the 100th anniversary of W. Oppenheim Söhne in 1933, with the company owner on the right (photos from family collection)

In 1933, the company V. Oppenheim & Söhne celebrated its 100th anniversary. However, the beginning of Nazi rule brought about considerable changes. Victor Carl's cousin Victor Nathan apparently saw no future for himself and his wife Julie in Germany, sold his share of the company to Victor Carl in the anniversary year and resigned from the company management. His view of the situation in Germany as so threatening may also have been influenced by the fact that his brother Julius had already been publicly humiliated and mistreated several times in 1933 and had been imprisoned for several weeks in the Breitenau concentration camp. Victor Carl, now the sole owner of the company, responded to the threat differently. In his study on the displacement of Jews from the Kassel economy, Horst Kottke states: "Victor Carl Oppenheim responded to the National Socialists' seizure of power with a far-sighted strategy. With effect from 30 June 1934, he acquired a silent partnership in the Kurt Kaufmann horsehair spinning mill in Basel. This made it easier for him to make a new start in Switzerland in 1939 after emigrating." (Kottke, p. 235) Before this happened, however, the horsehair spinning mill continued to flourish under Nazi rule. The consequences were initially more serious for the children of the family.

Getrud Oppenheim (Raya Livné)

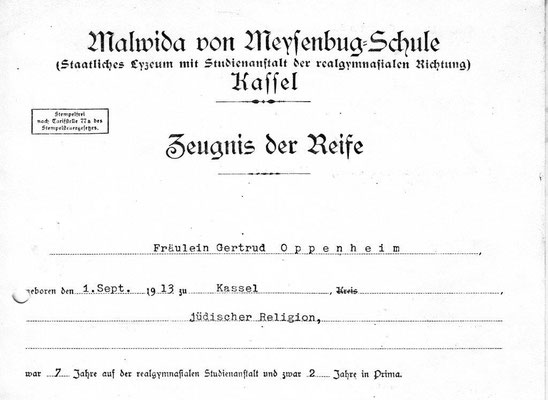

Getrud Oppenheim first attended a private school, then the Studienanstalt (since 1930 the Malwida von Meysenbug School), where she passed her school-leaving examination in 1934 together with other Jewish students. In her CV, written for admission to the Abitur, she writes about her sporting interests and extensive travels with her family to historical sites in Germany, but also in Greece and Italy, and above all about her decisive turn to Zionism: "But none of this could satisfy me in the long run. I realised more and more that only constructive work could fulfil my life. I joined the Zionist movement, which aims to reunite Jews scattered around the world in Palestine. Here I soon found my true calling, which fulfils me completely. I lead a group of eight to ten children aged around thirteen. I see my future in serving the Zionist idea. I intend to work in Palestine as a light current electrician. (...) I request that a note about my Jewish religious affiliation be included in my school leaving certificate.‘ Her original wish to study art history was impossible to realise for her as a Jew due to the ’Law against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Universities" of 25 April 1933.

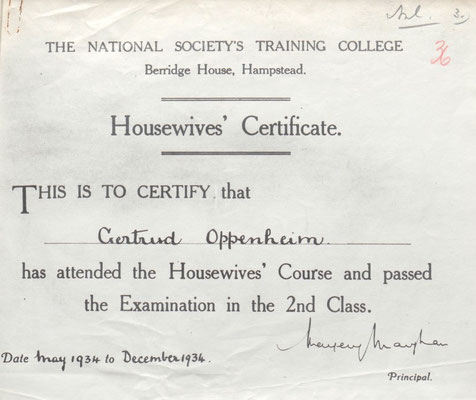

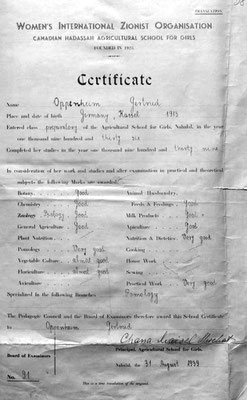

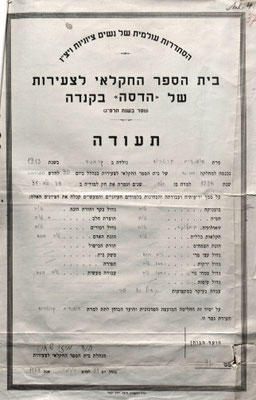

With the financial support of her parents, Gertrud first attended a domestic science school in England in 1934 and then, from 1936 to 1939, the Canadian Hassadah Agricultural School for Girls of the Women's International Zionist Organisation in Palestine, where she trained as a farmer. She took the name Raya Livné.

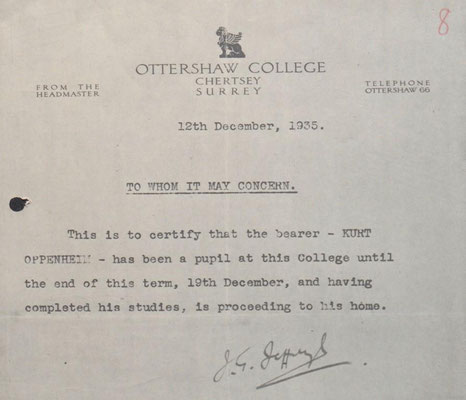

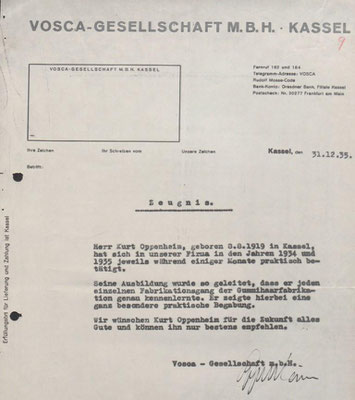

Instead of studying, training to be a housewife and farmer: testimonials from Gertrud Oppenheim.

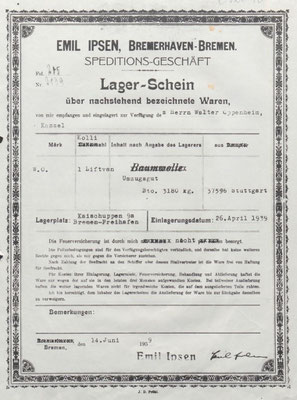

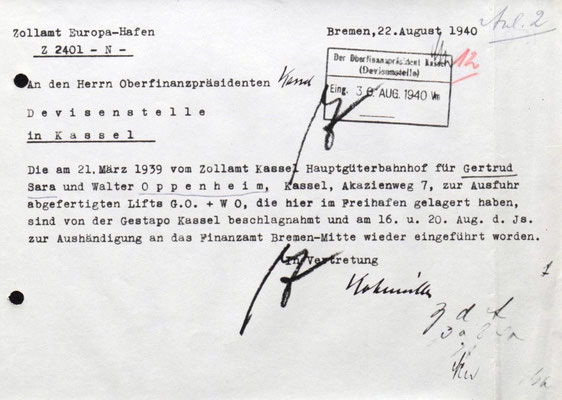

Gertrud officially emigrated in August 1937. In March 1939, her parents paid a considerable sum to obtain permission to send her belongings to Palestine in a lift. This was transported to Bremen by the Kassel-based shipping company Wenzel and stored there in the free port in April, but never reached its destination. It was confiscated in August 1940 on the instructions of the Kassel Gestapo and taken to the Bremen tax office. The German Maritime Museum is researching the fate of such lifts, and we therefore know that the lift belonging to Gertrud Oppenheim's uncle, Dr Leopold Oppenheim, which was also confiscated, was auctioned off to private individuals for a fraction of its value, with the proceeds going to the Reich Main Treasury.

In 1945/46, Raya Livné trained as a dressmaker in Basel, where her parents were now living, and worked in this profession in her home in Rehovot, Israel. She also became a state-certified tour guide and accompanied tourist groups from Germany. She died in 1996 at the age of 83, leaving behind a daughter, Rachel, and a grandson, Shaul.

Walter Oppenheim

There is no precise information about Walter Oppenheim's education. He probably attended a secondary school, but left during the Nazi era because of the anti-Semitism he encountered there. Apparently, like his brother and sister, he completed his education abroad before 1938. An affidavit from his mother in 1955 indicates that he travelled from abroad to Frankfurt in early 1938 to train as a locksmith. The Gestapo arrested him as an illegal immigrant, and he was imprisoned for three weeks in the police prison in Kassel at the Königstor before being released at the instigation of lawyers.

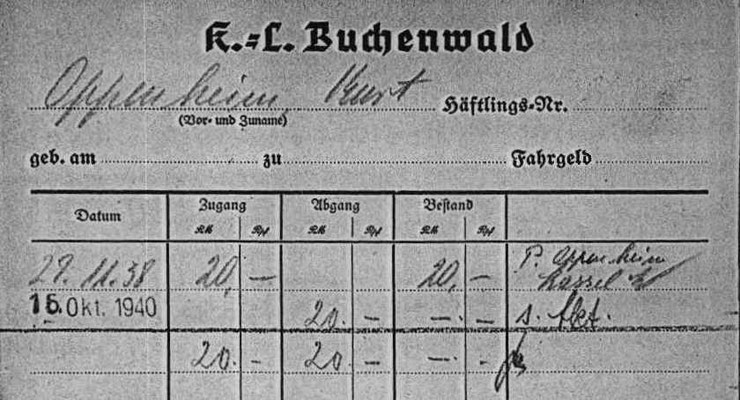

In November 1938, he was among more than 250 Jewish men from Kassel who were arrested and imprisoned for weeks in a special camp at Buchenwald concentration camp, where all the extremes of the concentration camp were intensified. The main aim of the action was to force these prisoners to emigrate and thus drive them out of their homeland.

Money cards’ belonging to Walter and Kurt Oppenheim from Buchenwald concentration camp and photo of a roll call of so-called ‘action prisoners’ in November 1938.

Shortly after his release from the concentration camp in December 1938, Walter Oppenheim made his way to Wieringen in the Netherlands and later to Palestine. The lift packed for him in 1939 and stored in Bremen suffered the same fate as his sister's.

Walter acquired citizenship of the Mandate of Palestine (later Israeli citizenship) and married Marianne David, who was from Hamburg, in 1941. In 1942, he joined the Royal Army Ordnance Corps of the British Army and was deployed as a driver in Italy. While on holiday with his parents in Basel, the now divorced Walter met Ruth Rueff, a Swiss woman, and became engaged to her. The marriage, which was solemnised in 1946 by a British army chaplain, was dissolved a year later. Walter Oppenheim, who had fought in the Israeli War of Independence, died in 1954 in Chedera, where he was probably working as a farmer, leaving behind his son Victor Claude.

Storage receipt for Walter Oppenheim's lift, its seizure (HHStAW) - Walter Oppenheim in Israel

Kurt Oppenheim

Like his older brother Walter, Kurt Oppenheim did not successfully complete secondary school, but was unable to remain there in 1934 ‘due to the anti-Semitic attitude of the teachers and fellow students,’ as he wrote after the war. In view of the adverse circumstances of the time, however, his parents obviously did everything they could to ensure that he was still trained to take over the business. Kurt attended college in England from 1934 to the end of 1935, then a higher commercial school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, during which time he did internships at his parents' company, VOSCA GmbH (rubber hair manufacturing), during the holidays. These were prerequisites for his entry into his father's company, where he had been working in a practical and commercial capacity since August 1937. The aim was ‘to enable him not only to work as a specialist in every single department of a horsehair spinning mill and to acquire sufficient knowledge of raw materials and finished products, but also to enable him to take over the management of a business,’ according to a preliminary certificate dated 31 December 1938.

At that time, Kurt, like his older brother, had spent several weeks in Buchenwald concentration camp. He complied with the order to leave Germany in March 1939, when he reached England, where he remained, although his actual destination was probably the United States. In 1940, like many German emigrants, he was temporarily interned as an enemy alien. In London, he married Lilli Blum, who was originally from Vienna, in 1942.

The youngest child of the Oppenheims succeeded in continuing the family's industrial tradition in England. After the war, he founded a factory in Cumberland for processing animal hair and successfully converted it to the production of urethane foam in the 1960s, when plastics replaced natural materials. He sold the company, which employed several hundred people, in the 1970s and retired to London, where his three children, Frances, Diana and Denise, lived. Kurt died in 2003. Of his children, only Frances is still alive (2025), and she was the one who suggested laying the Stolpersteine. .

The parents and the horsehair spinning mill

While the children, as in many Jewish families, were already abroad, Victor Carl and his wife Paula decided late to emigrate and, compared to other entrepreneurs, very late to sell the family business. Perhaps this had something to do with the fact that Victor Carl's parents, both of advanced age, were still living in Kassel in 1939. He escaped arrest during the November pogrom, when his house was searched, because he had been hiding in another location for a long time. In January 1939, he took the Hebrew name Awigdor (which can also mean Victor in German) to avoid being forced to take the name Israel.

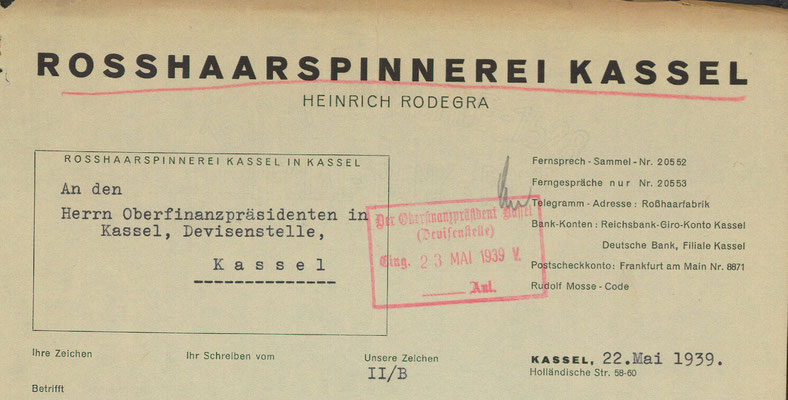

Based on Victor Carl's income, the horsehair spinning mill apparently suffered hardly any loss of earnings, in contrast to other Jewish businesses. Victor's private fortune was still considerable in 1938, amounting to around 500,000 Reichsmarks. It was not until March 1939 that he sold the company to Heinrich Rodegra, a German living in Riga, for approximately 144,000 Reichsmarks. In 1940, the district president officially described this as the ‘de-Jewification of the horsehair spinning mill’. Rodegra paid the purchase price by transferring funds to emigrant blocked accounts, which could not be freely disposed of, and half of the amount directly to the tax office to settle the Reich flight tax. After the sale of the company, the couple emigrated to Basel, where Awigdor had been a partner in the Kaufmann horsehair spinning mill since 1934.

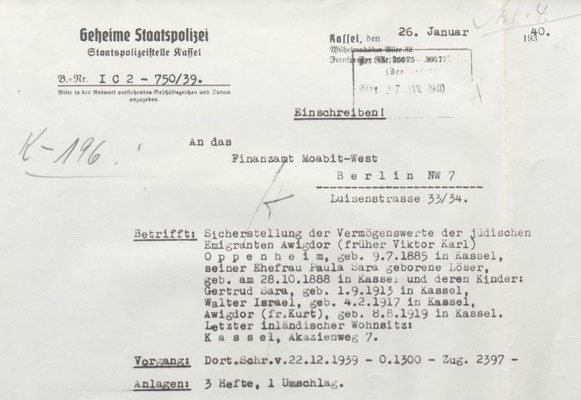

In December 1939, the Reich revoked the citizenship of all family members, which was accompanied by the confiscation of all their assets. On the instructions of the responsible tax office in Berlin-Moabit, the Kassel Gestapo took care of this.

Letterhead of the new owner – Letter from the Kassel Gestapo regarding the seizure of assets (HHStAW)

After the war, the family fought for restitution and compensation for the losses they had suffered. This included, among other things, the payment of the Jewish property tax, the Reich flight tax, the emigration tax to the Jewish community in Kassel (which was intended to help needy community members) and the levies to the Golddiskontobank (in connection with the transfer of removal goods or foreign currency transfers abroad). The restitution proceedings concerned the forced sale of the company and the villa at Akazienweg 7, as well as other properties in Kassel and Berlin, the stake in the Pincus wool laundry, and finally the confiscation of valuables and the household goods of all family members, which were of considerable value.

In Basel, Victor Carl worked as a ‘working partner’ in the Kurt Kaufmann company, in which he had held a stake since 1934, until 1945, after which he spent several years as director of the newly founded ‘Rosshaarspinnerei Basel’ (Basel horsehair spinning mill). He died in 1960, his wife Paula in 1962.

Victor Carl's father Max died in Kassel a few weeks after his son's emigration in June 1939, while his mother Johanna was able to join her eldest son in Palestine in the same year, where she died in July 1943. Victor Carl's brother Dr. Leopold Oppenheim, managed to escape to London just a few days before the war began, where he resumed his career as a lawyer after the war – not least as legal counsel to former residents of Kassel. Like Kurt Oppenheim, he also called himself Awigdor.

The laying of the Stolpersteine was initiated by Frances Taylor. SMMP Holding, the school authority responsible for Engelsburg-Gymnasium, provided the funding.

Quellen und Literatur

HHStAW

Best. 518 Nr. 68922 und 68891 (Entschädigungsakten Victor Nathan Oppenheim) | Best. 519/3 37198 (Devisenakte Rosshaarspinnerei)

Best. 518 Nr. 39989, 68865, 68896 und 68924 (Entschädigungsakten Victor Carl, Gertrud, Walter und Kurt O.

Best. 519/2 778 Bd. 1-2 (Einkommenssteuer- und Devisenakte Victor Carl O.)

Stadtarchiv Kassel

S17 Nr. 30 (Familie Oppenheim) | Adressbücher | Hausstandsbücher

Arolsen Archives

Dokumente aus dem KZ Buchenwald zu Kurt und Walter Oppenheim

Schularchiv der Heinrich-Schütz-Schule Kassel

Dokumente zum Abitur 1934

Fotos und Informationen zur Familie von Frances Taylor

Horst Kottke, Die endgültige Verdrängung der Juden aus der Kasseler Wirtschaft im Jahre 1938, in: Wilhelm Frenz/Jörg Kammler/Dietfrid Krause-Vilmar, Volksgemeinschaft und Volksfeinde, Bd.2, Fuldabrück 1987, S. 223ff.

Dietrich Heither/Wolfgang Matthäus/Bern Pieper, Als jüdische Schülerin entlassen. Erinnerungen und Dokumente zur Geschichte der Heinrich-Schütz-Schule in Kassel, Kassel 2. Aufl. 1987

Deutsche Schifffahrtsmuseum, Lost Lift Datenbank

Wolfgang Matthäus

Juni 2025

Verlegung am 2.7.2025

Stolpersteine in Kassel

Stolpersteine in Kassel